ANTIQUARIAN & SECONDHAND BOOKSELLERS

Proprietors: Camilla Francombe & Stuart Broad

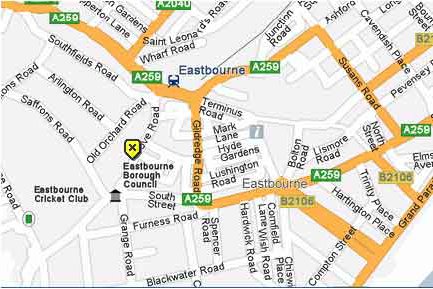

57 Grove Road, Eastbourne, East Sussex. BN21 4TX. UK

Tel: + 44 (0)1323 736001 - Email: camillas.bookshop@gmail.com

'Archie' (our parrot) is in residence in our shop all day every Tuesday & Friday. He loves a good audience and a sing-song!

We are a very large Secondhand & Antiquarian Bookshop located a five minutes walk from Eastbourne Railway Station. From the railway station, go up Grove Road, past the library for 400 yards. Our shop is situated on the right hand side next to the Grove Road Medical Practice.

Opening Hours: Open all year round except Bank Holidays and Christmas/New Year. 10.00 - 17.00 hrs Monday to Saturday.

We have in excess of one million books in stock with a proportion listed on abebooks.com, amazon.co.uk and biblio.com.

We accept credit and debit cards, and PayPal transactions.

We are able to ship consignments of books worldwide at competitive rates.

"Amazing secondhand bookshop" The Guardian

"Eastbourne's saving grace" The Spectator

Our Specialities: Armed Services - Transport - Travel Literature - History - Music - Art - Religion - Sport - Poetry & Literature - Modern First Editions.

We buy books - call us on 01323 736001

News update

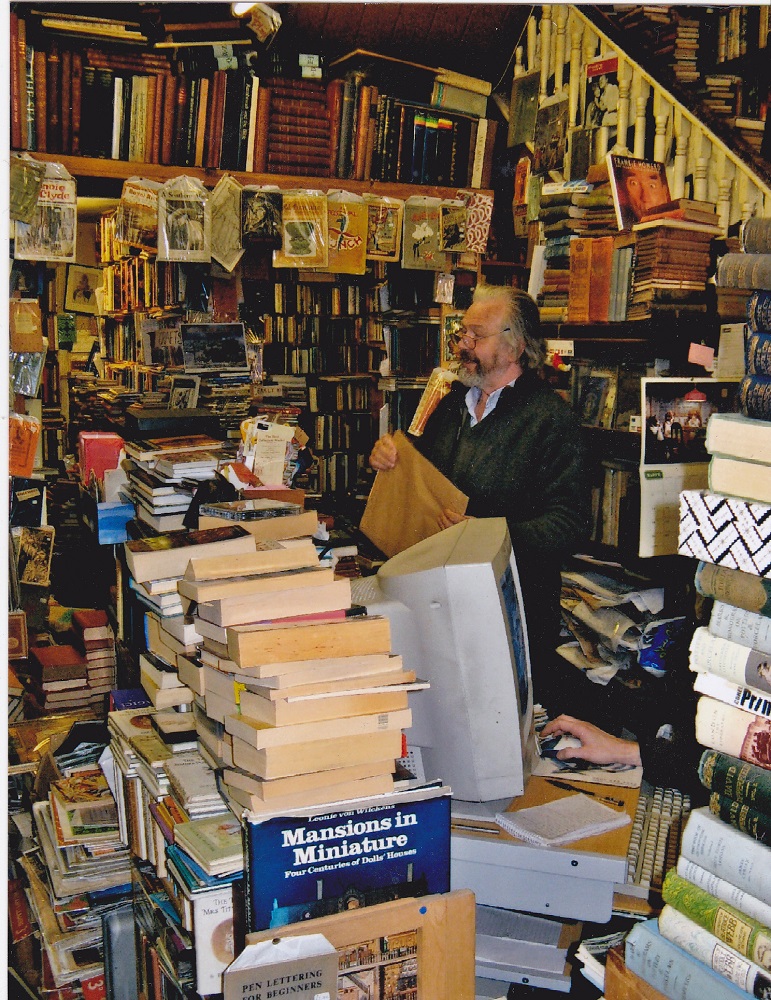

Stuart and Camilla - the two proprietors!

Stuart in action!

Article in Eastbourne Herald - 15th August 2014

We're talked about in the New Statesman - 8th July 2014

Choices, choices: could I be a bookshop?

Robin Ince

Hints of paranoia dog me, the sense of being scrutinised – but that all evaporates in the bookshop. Most of my working life is trains. I go from town to town, like the Fugitive or David Banner, but without the sense of pursuit by law-enforcers.

My earnings are not for the show I will do in the evening – that is pleasure. They cover the cost of being away from my family and sitting on a packed train, positioned somewhere between an overflowing bin and a malfunctioning toilet. I occupy my time experiencing train theatre, the small playlets of anger, desire and melancholy that take place in the seats and vestibule area. The furious phone calls with alibis from drunken business people explaining they were kept late at work; the sad-faced man who failed to press the lock button on the toilet, now shrivelled after shrieking, “Close the door!” with his trousers round his ankles and his newspaper on his lap. The door will not close until it has opened fully first – and so all the travellers have experienced a Beckett short adapted by Ray Cooney.

But most of my time is spent in other worlds, in the pages of the second-hand books that increasingly bulk up my rucksack as I investigate the bookshops of each town I visit.

The carriage is not a means of transport. It becomes a hectic library, where I can drink tea, flick the crumbs of my cake from the hinge of a book, and read on, occasionally looking up to view alpacas on disused factories, or hillsides. While at night I must be gregarious with a few hundred people, by day I can be solitary.

My greatest joy is browsing books in seaside towns. There I am lost. The delight of the second-hand bookshop is the delight of surprise. New bookshops are pleasurable but we know what lies within. Yet in the second-hand, who knows what nonagenarian ufologist or furtive philosopher has died and their boxed books have found their way on to the counter.

I am rarely looking for anything in particular. I am looking for everything in particular. Many of my childhood weekends were spent with my father, browsing through bookshops with warped shelves and idiosyncratic cataloguing techniques. Nature and nurture have combined to make me an obsessive.

Desmond Morris once described the finding of a rare book as being the modern equivalent of stalking and killing mighty prey. The tribe rejoices. I am not sure my wife has the same sense of glee when I bring back another satchel of Pelicans and Penguins. Sometimes I find myself taking the back footpath and popping them under the shed until she has gone out. I fear that one day my house will sink into the ground, leaving visible only a chimney pot. Just as John Peel had to reinforce the foundations of his garage to support the weight of vinyl, I may have to call the architects in.

I see myself as an overly self-conscious human being. Hints of paranoia dog me, the sense of being scrutinised, yet that all evaporates in the bookshop. I am mesmerised by the spines – almost unconscious, until I see something with an alluring title or enigmatic cover.

Then it’s the leafing through. Do I need this book? What weight is my rucksack already? Is this purchase worth the extra tingling of sciatica it may bring on? My mind must map the shop. The most labyrinthine are a delightful challenge. When I get to the end of the browsing, I must recall where each possibility is and return for a decision.

Once the books are bought, I retreat to a tea shop, preferably one with an elaborate Victoria sponge in the window, and pore over the new purchases. Inside each book is the hope of a new way of seeing the world; each one is a potential adventure. There can be the additional joy of finding some ephemera left by the previous reader: a pressed flower, a bookmark, an old postcard of Budleigh Salterton sent by “Isobel”, with the story of a beach hut and errant gull.

I like losing myself in those shops that were once houses, where each room is book upon book – and perhaps sheet music and some National Geographics. As a child, I went to the Cottage Bookshop in Penn, its rows so narrow it was barely possible to tilt your head back far enough to read the upper shelves. The attic room had a lock on it; not due to the madness of the owner’s first wife – this was where the collectibles were kept, and sometimes I snuck in with my dad. And no trip to Eastbourne is complete without a visit to Camilla’s. Should all the bricks disappear, the structural integrity would remain from books alone. There is a tea shop two doors down; its cakes are mighty.

Some people wish to be buried at sea, others scattered on a hillside. I wonder if the matter that makes me could be transmogrified into a bookshelf?

Robin Ince is on tour and will be appearing at the Latitude Festival on 19 and 20 July.

http://www.newstatesman.com/culture/2014/07/after-god-how-fill-faith-shaped-hole-modern-life

*************************************************************************

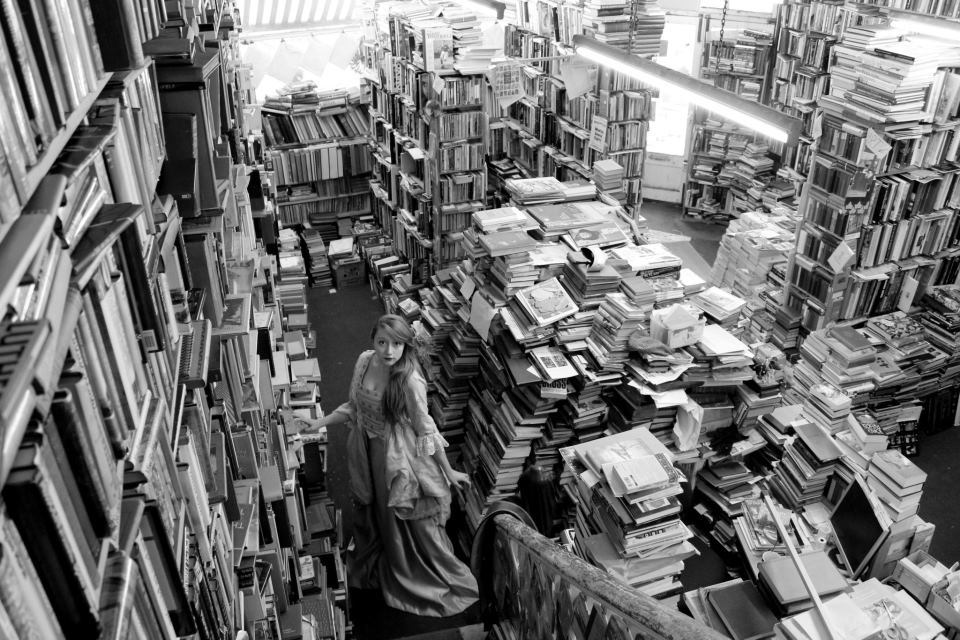

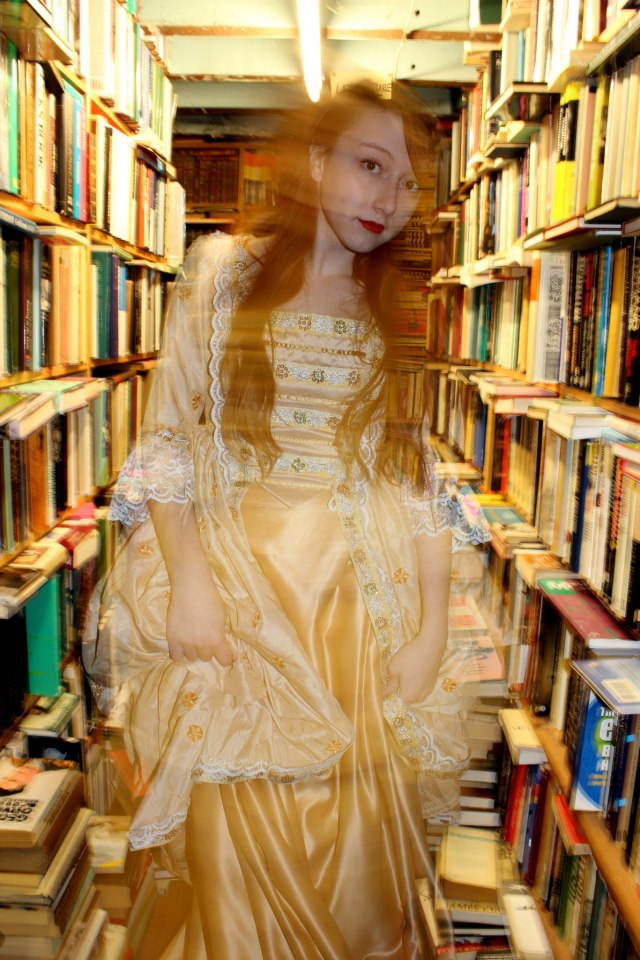

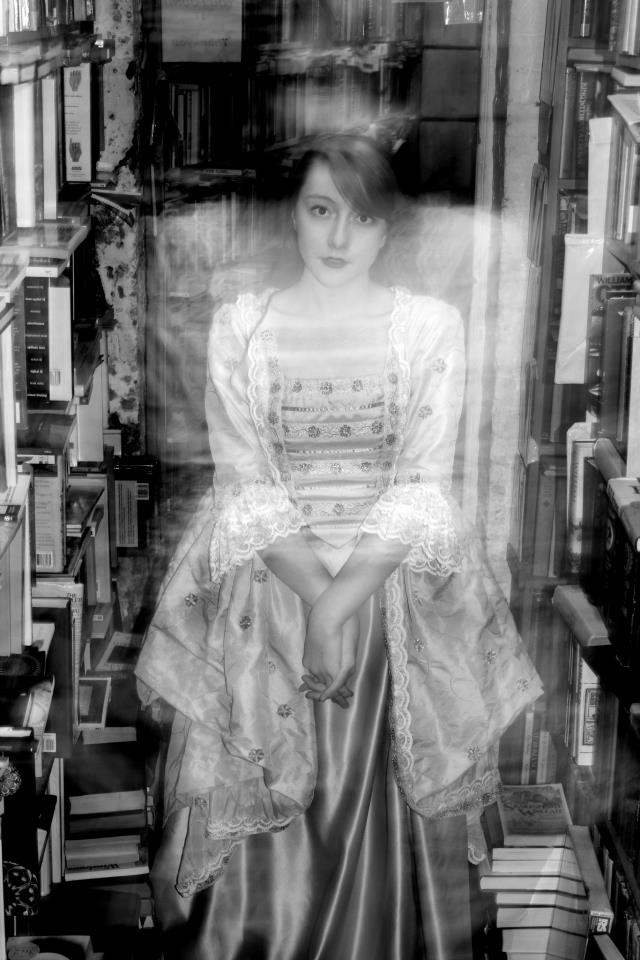

Four images of a Victorian dress fashion shoot done on location in Camilla's Bookshop, Winter 2012.

Images courtesy of Rachel & Charley: photography students at Sussex Downs College, Eastbourne, East Sussex. 2012

*************************************************

Here is a link to a blog about Penguin Books, on which there is considerable mention of Camilla's Bookshop.

http://apenguinaweek.blogspot.

**************************************************

Below is an extract from an article mentioning Camilla's Bookshop, found on the website of the Catholic Herald.

'One thing about travelling, especially in a country where English is not widely spoken, you really do need to take your reading matter with you. I have resisted the temptation to get a Kindle, and have stuck with my very heavy breviary, and have brought a few books with me. Just before setting out, I had nothing to read, so I visited the best bookshop I know, Camilla’s in Eastbourne. It is a secondhand bookshop which occupies a whole house quite near the station, just opposite Our Lady of Ransom. The owner sits at his desk in the main room downstairs, surrounded by his stock, literally walled in by books, so he is quite hard to spot. One has the impression of walking into a quite silent almost sacred space, until one is taken by the suprise of seeing the owner sitting in quiet contemplation of his books.

I told him that I would have liked to buy far more than the twenty or so books I was able to carry away. “You can have the whole lot for a million quid,” he said levelly. That would work out at about a little more than two pounds a volume, I suppose.

Camilla’s does not specialise as such, as far as I can see, though there is a whole room more or less dedicated to militaria, and there were plenty of Books of Common Prayer, but no old Missals. There is a whole room in the cellar that I missed (I will save it till another time) which contains Latin texts. The poetry is excellent. I have been trying to make up for my previous neglect of the great Victorian poets, whom I somehow wiggled out of reading at University: with me in Mexico I have two manageable volumes containing the complete works of Keats and Byron, ideal companions for solitary meals in restaurants.'

Fr Alexander Lucie-Smith - CatholicHerald.co.uk - 8 February 2012.

****************************************************

'Half a Million Books'

Gerda Babiedaite, a television production student at Brighton University, made a 10 minute documentary about Camilla's Bookshop in December 2011. The film is now up on YouTube and can be viewed by clicking on the image above.

*****************************************************

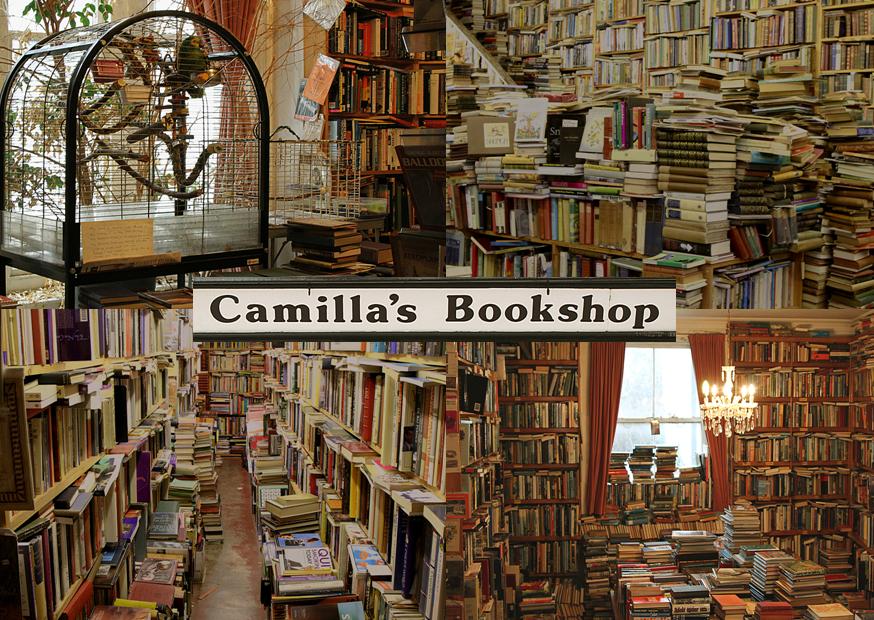

Our new postcard is available in the shop at 25p each

*****************************************************

Camilla's Bookshop was used as a film location in June 2011. A short film entitled 'Fishing' was made which tells the story of a magical bookshop that prevents the shopkeeper from escaping. He has to go to extreme lengths to escape. Click on the image above to access the film website.

*******************************************************

Website updated on Friday 26th December 2014